The mission of the Latino Leadership Alliance (LLA) is to empower Silicon Valley Latino leaders to promote a common voice that addresses the interests of our community, and to identify, develop, and support future leadership. ~ Adopted by LLA Cofounders, 2005

***

During the summer of 2004, while hiking in the Sierras as a Class XVIII fellow with the American Leadership Forum of Silicon Valley (ALF-SV), I thought about creating a similar organization that could train emerging Latino and Latina community leaders to manage the complex world of civic leadership. I shared the idea with a couple of Latino and Latina elected officials. They convened a group of eight community leaders to brainstorm ideas to create such an organization.

The group included San Jose City Councilwoman Nora Campos, San Jose Planning Commissioner Xavier Campos, San Jose City Councilwoman Cindy Chavez, Santa Clara/San Benito Counties Building Trades Council Executive Josue Garcia, East Side Union High School District Trustee George Shirakawa, MACSA Executive Director Olivia Soza Mendiola, and Mt. Pleasant Elementary School District Trustee Fred Tovar. As the eighth member of the group, I was a junior executive at Comcast and board chair for the Mexican Heritage Corporation.

Over the course of several months meeting in living rooms, we established a name for the organization, adopted a mission statement and core values, and discussed the concept for a leadership academy. By early 2005, we established the Latino Leadership Alliance (LLA) “to empower Silicon Valley Latino leaders to promote a common voice that addresses the interests of our community, and to identify, develop, and support future leadership.” Guiding our work were seven core values:

- Cultural pride is the foundation of our success.

- Honor and integrity guide our every action.

- When united we are an effective force.

- Our community deserves to be respected and portrayed honestly and fairly.

- We are committed to leading and nurturing the community that nurtures us.

- Our united presence and influence are vital to the success of the community.

- We will never take money or support those who harm the Latino community.

I eagerly accepted the task of developing the leadership academy. The eight Cofounders agreed that the academy should focus on three overarching objectives: (1) servant leadership, (2) practical (as opposed to theoretical) application of leadership, and (3) challenges of serving the community as a Latino leader. As senior fellows with the ALF-SV, we were inspired to base the academy on that proven model. I also included elements of the Comcast Executive Leadership Forum, a program I benefitted from as a young and ambitious junior executive.

Both programs included three major components: (1) monthly seminars, (2) leadership retreat, and (3) alumni network. To ensure that the Cofounders’ shared commitment to preparing participants for civic leadership was covered, I developed the Four Pillars of Community Leadership model (Business, Nonprofit, Education, and Politics/Government) based on my career experience working in each pillar.

An early challenge was creating a leadership retreat from scratch. The ALF-SV retreat is a week-long camping trip in the high Sierras. Cofounders were in agreement that operating the academy should be affordable to participants. A wilderness retreat was financially out of the question. The Comcast ELF retreat was a week at the company headquarters in Philadelphia. Comcast senior executives and college professors served as presenters. That concept led to the idea of the LLA collaborating with a university.

What happened next could be a scene from a feel-good movie or maybe a sitcom. Three of us, including fellow Cofounder George Shirakawa, drove north on U.S. 101 to meet with Professor Al Camarillo, the legendary Father of Chicano Studies . . . at the Stanford Faculty Club! We were excited about the opportunity just to be there, making jokes about three traviesos from east San Jose in the distinguished Stanford Faculty Club without supervision to meet the university’s most decorated professor. What could go wrong?

Professor Camarillo was down to earth and “one of us.” He praised our presentation and supported our proposal. Under his leadership, the LLA would collaborate with Stanford’s Center for the Comparative Studies of Race and Ethnicity. We had the final piece needed to build a solid leadership academy that would be culturally relevant to our experiences as civic leaders in a political environment that isn’t always accommodating or friendly to Latinos.

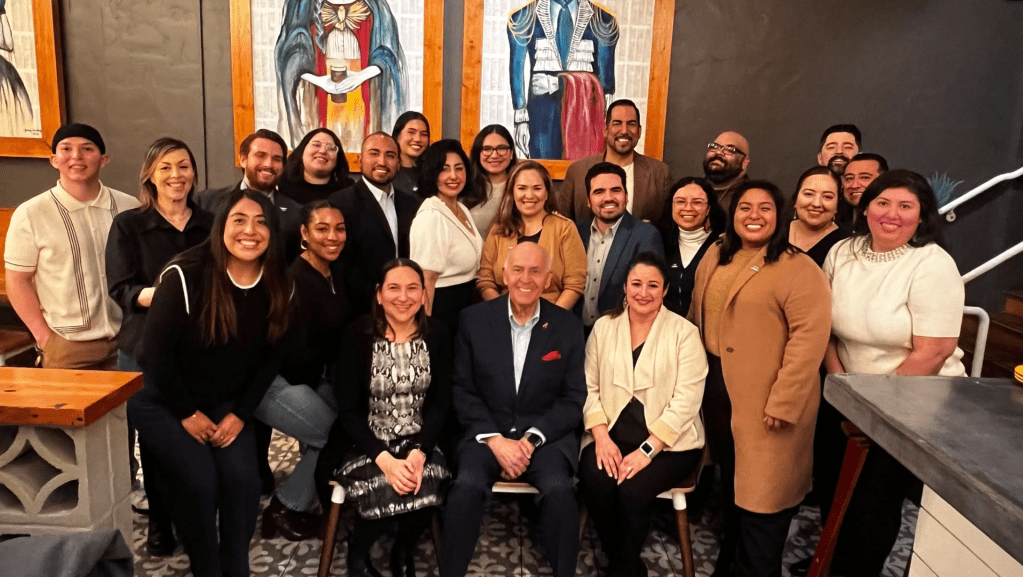

The Academy consists of twelve to fourteen participants from the business, education, nonprofit, and political/government sectors. The cohorts engage in eight monthly full-day seminars that include workshops, reading assignments, leadership exercises, and guest speakers. The monthly seminars are held at a variety of places in the community. During the summer, the cohort spends three days and two nights with university faculty at Stanford.

Participants learn about five major leadership concepts: (1) Servant Leadership, (2) Relationship Development & Management, (3) Living and Leading Holistically, (4) Civic Engagement, and (5) Leadership Communications. The LLA Stanford Summer Leadership Institute is developed and coordinated by Stanford faculty. The capstone to the program is the Cohort Community Project developed and executed entirely by the cohort participants. In early 2010, the inaugural cohort of the LLA Leadership Academy and Stanford Summer Leadership Institute served as the beta test. Fifteen cohorts have completed the program through September 2025.

The LLA Alumni Network includes 184 members who have made significant contributions to community life in Silicon Valley. Eight alumni served or currently serve on city councils in three different cities. Nine alumni served or currently serve as trustees on five different schools boards. There are scores of LLA alumni serving as local government commissioners and nonprofit board members.

LLA-trained business and nonprofit executives, and public school administrators and superintendents serve the community with cultural relevance and skill. In 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom appointed a LLA alumnus to serve as a judge in the Santa Clara County Superior Court. By all measures, the LLA Leadership Academy and Stanford Summer Leadership Institute has been an overwhelming success.

My professional career included four distinct periods. While each of those experiences holds a special place in my journey, the creation and development of LLA combined all four into one passion – sharing my experiences to support talented civic-minded and career-focused Latinos and Latinas on their leadership journeys. For 21 years, LLA has been my life’s work.

On June 7, 2025, I sent a letter to the LLA Board of Directors to announce that Cohort 15 would be my last. It was a difficult decision with a practical purpose. It’s important for leaders to have the wisdom to hand over the keys to the next generation so the organization can grow and thrive. The time was right for LLA to forge a path into the future without my support. Although my door is always open to LLA alumni, my work here is done.

As I say goodbye to LLA, my heart is filled with gratitude and accomplishment. There are too many individuals to thank, so I’ll do it in groups. First and foremost, I have deep respect and appreciation for my fellow Cofounders for having the vision, courage, and determination to bring an overdue idea to life. Thank you for your confidence in me to develop the Academy in collaboration with your guidance. We had our share of challenges and trials in building the LLA. Our commitment to be united, stay true to the mission and core values, and leave our titles and personal political agendas at the door ensured that we weathered any and all storms.

Second, thank you to the twelve cohorts and 145 participants I had the privilege to work with while facilitating the Academy. You all are valued leaders in the community. Third, thank you to the many guest speakers and panelists who took precious time from their busy schedules to share their wisdom with our cohorts. I’m also grateful for the private companies, school districts, nonprofit organizations, city council members, and county supervisors for generously providing space or monthly seminars over the years.

Last, but certainly not least, two individuals warrant special acknowledgement. Thank you, Dr. Al Camarillo for taking a chance on a LLA. The Stanford collaboration has been the hallmark of the Academy. Thank you, Dr. Tomas Jimenez for carrying the torch and for your continued commitment to LLA. I appreciate and value the partnerships and our friendship.

It’s been an honor of a lifetime to work with all the people it takes to make the LLA Leadership Academy and Stanford Summer Leadership Institute the premier Latino civic leadership development organization in the Bay Area. All I can do is humbly offer my deepest appreciation and respect for you all.

As time goes on, LLA is sure to expand and explore different leadership development models. My hope is that the current board leadership and future LLA leaders find wisdom in the core values envisioned by the Founders. If they conduct the organization’s business with those values in mind, LLA’s future is without limits!

Once again, thank you LLA! It’s been an amazing journey.