Part 1

The Mexicans

November 29, 1777 ~ November 3, 1980

When Neve (Governor of Alta California, New Spain) reported to the viceroy that the Guadalupe area would make an excellent town site, he requested 40 to 60 colonists, all experienced Mexican farmers with families, be recruited.

~Edwin A. Beilharz, Santa Clara University Professor and Author, San José, California’s First City, 1980

* * *

San José, California, has existed as an organized governmental pueblo, town, or city for 248 years. Despite being the first civil settlement in California, San José has few published historical works. Fredric Hall, an obscure attorney and amateur historian, conducted extensive documentary research and kept a diary of his youth in San José to write The History of San José and Surroundings, published in 1871.

A century later, Santa Clara University history professor Edwin A. Beilharz and Donald O. Demers published a coffee-table book titled San José, California’s First City as part of a series on local history from Continental Heritage Press. Beilharz and Demers acknowledge the presence of Mexicans in San José’s history but offer no in-depth analysis of its implications for the city’s development.

During that same period, an amateur historian named Clyde Arbuckle was encouraged by a fellow history buff to write the “definitive” History of San José. When Arbuckle published the book in 1985, the foreword stated, “In these pages we will relive the founding and emergence of our city as recounted by one who knows it better than any other.”

It’s important to note that Arbuckle was not an academically educated or trained historian. In fact, he dropped out of high school at 15 to work as a laborer in a printing shop and ultimately spent 25 years as a delivery driver for the firm. He took a few history classes at night school and became quite the history buff. In 1945, the City of San José named him the official City Historian, most likely because he had a passion for the community’s past.

Nevertheless, Arbuckle’s book is detailed and well-researched. While the statement in the book’s foreword that Arbuckle knew the city’s history “better than any other” may have been accurate, the History of San José author only tells part of the story. Arbuckle makes no mention of the Mexican presence or contributions to San José’s development. His retelling of the Pueblo’s founding in 1777 occupies only four paragraphs in a book spanning 535 pages.

Aside from an odd statement asserting that the settlers “were not the best material in the world for their task,” Arbuckle provides no historical analysis at all, especially with respect to the people who settled on the banks of the Guadalupe River. How Arbuckle concluded that the settlers “were not the best material” is anyone’s guess.

In an April 15, 1778, letter to superiors, Felipe de Neve, Governor of Alta California, New Spain, wrote that he assigned “nine soldiers with farming experience” to settle El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe. Fredric Hall’s 1871 book describes the settlers as “skilled in agriculture.” Those accounts confirm that the settlers were the best material for developing an agricultural community.

Whatever the reason for Arbuckle’s omission of the Mexican experience in San José, his manuscript does not provide a comprehensive or definitive history of the city and perpetuates the false narrative that Spaniards founded the pueblo.

It wasn’t until 2003, when Yale historian Stephen J. Pitti published The Devil in Silicon Valley, that historical works about San José correctly identified the Pueblo’s founders as “ethnic Mexicans.” In 2025, San José State University historian Gregorio Mora-Torres wrote a comprehensive account of what he calls the ethnic Mexican experience in San José.

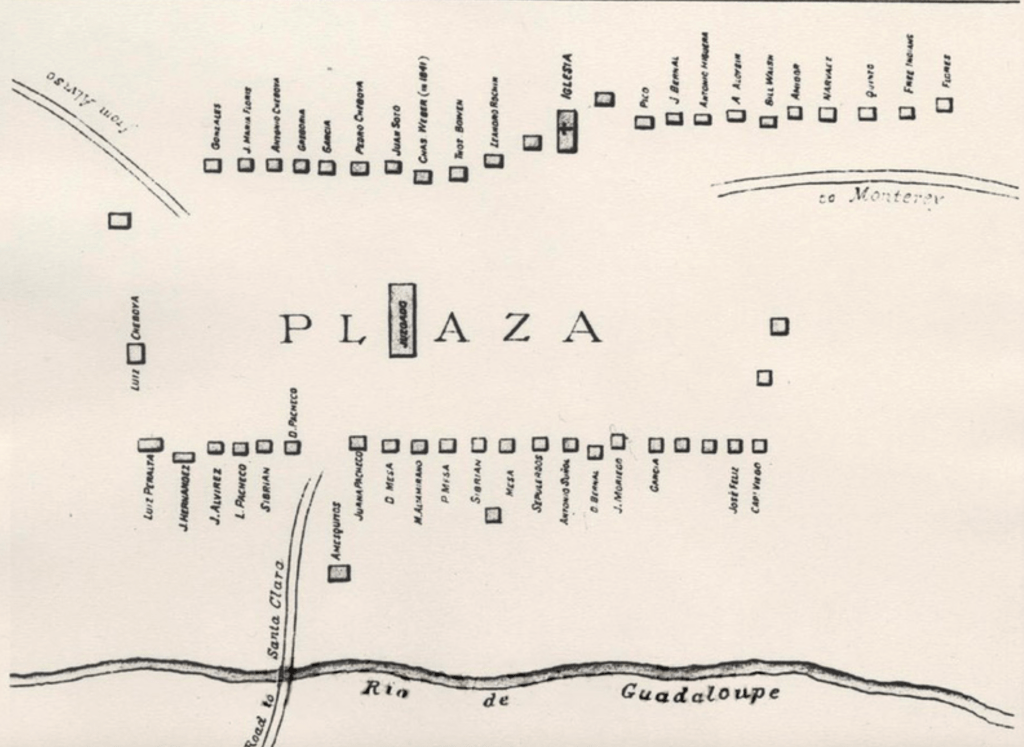

The facts, as chronicled by Beilharz, Pitti, and Mora-Torres, are that each person in the small band of 66 pobladores (settlers) who pitched camp along the Guadalupe River was born in México, including the “Spanish” army captain José Joaquín Moraga, who led the expedition. He was born at the Mission Los Santos Ángeles de Guevavi in Sonora, México (now in modern-day Arizona).

Within a few years, San José’s settlers were producing enough food to feed the military presidios in Monterey and San Francisco. By the mid-1780s, the pueblo’s leaders established a thriving community. Although still under the King of Spain’s royal authority, the Mexican settlers produced abundant crops. They established a “town council” in San José, launching a form of self-government for the faraway outpost settled by people from Sonora and Sinaloa, México.

In 1846, U.S. troops invaded México in a war of conquest. On the eve of the war, four out of every five people living in the Pueblo were Mexican. Through intermarriage and legal sleight of hand after the 1846-48 American War with México, Mexicans began to lose their land and influence in San José gradually.

By the 1880 U.S. census, Mexicans made up only 6% of the town’s population. This number is likely inaccurate as American officials probably undercounted Mexicans. Nonetheless, the Mexican population decreased significantly in the three decades following American statehood.

While ethnic Mexicans seemed to disappear from the written annals and minds of the white business and ruling class in San José, they continued to thrive and contribute to the city’s development. Over 1,000 miners from Sonora, México, lived and worked in the quicksilver mines in the southern hillsides known as the misnamed Spanishtown. Immigrants from México and native-born descendants of the founders led cattle drives, cultivated crops, picked fruit, and worked in the growing canning industry, which was the valley’s economic engine.

By the mid-20th century, a burgeoning ethnic Mexican middle class had emerged. The Mexican neighborhoods west of downtown thrived, with businesses lining Market Street. Dance halls hosted local talent and major musical acts from México. Radio programs featured personalities that read the news in Spanish and played the latest popular Latin music.

During the late 1960s, Mexican and Mexican American business and community leaders were poised to take civic leadership roles in a town that their ancestors had founded almost 200 years earlier.

***

Note: Stay tuned for more information about the release of Mexican Heritage Plaza: A Symbol of Resilience and Perseverance